St Vincent’s: Church History

Scotland’s religious history has been characterised by schism and reunion. By the late 18th century the Episcopal Church consisted of congregations under the jurisdiction of bishops who traced their orders back to the Scottish episcopate which had refused to accept the Revolution Settlement of 1689 and could fairly be described as Jacobite in sympathy. There were also ‘qualified’ congregations, their clergy usually imported from England or Ireland, which accepted the Hanoverian monarchy but not the jurisdiction of the Scottish bishops. The first group was proscribed by law from holding services attended by more than five persons, the second group could worship freely and, from 1750, built substantial churches in the major towns and cities.

Scotland’s religious history has been characterised by schism and reunion. By the late 18th century the Episcopal Church consisted of congregations under the jurisdiction of bishops who traced their orders back to the Scottish episcopate which had refused to accept the Revolution Settlement of 1689 and could fairly be described as Jacobite in sympathy. There were also ‘qualified’ congregations, their clergy usually imported from England or Ireland, which accepted the Hanoverian monarchy but not the jurisdiction of the Scottish bishops. The first group was proscribed by law from holding services attended by more than five persons, the second group could worship freely and, from 1750, built substantial churches in the major towns and cities.

After the death of Prince Charles Edward Stewart, the Young Pretender, in 1792 the Scottish bishops formally accepted George III as king and the penal laws were repealed. From the early 19th century the ‘qualified’ congregations accepted the jurisdiction of the Scottish bishops and the Scottish Episcopal Church, in communion with the Church of England but autonomous, was established as a denomination.

By 1840 many Scottish Episcopalians were increasingly influenced by the teachings of the Oxford Movement which stressed the historic continuity of Anglicanism with the apostolic and medieval Church and gave fresh importance to sacramental worship. The Holy Communion liturgy of the Scottish Prayer Book, first promulgated in 1637 but revised as the Scottish Communion Office of 1764, was seen as more sacramental than the equivalent service in the English Book of Common Prayer, although both services were used by Scottish Episcopalians.

The shift towards Catholic ideals was not welcomed by all. In 1842 the Reverend David Drummond, a curate at Holy Trinity, Dean Bridge, Edinburgh, seceded from the Scottish Episcopal Church, declaring himself to be in communion with the still predominantly ‘Low’ Church of England but rejecting the authority of the Scottish bishops, and built a chapel, St Thomas, for himself and his adherents in Rutland Place. Ten years later, Drummond appointed an Evangelical English clergyman, Richard Hibbs, as his curate.

The association was unhappy and in 1854 Hibbs left St Thomas’ to found his own Church of England congregation. He acquired a vacant plot of land on the comer of St Vincent Street and St Stephen Street on the edge of Edinburgh’s Northern New Town and, in 1856, commissioned designs for a chapel.

Hibbs’ chosen architects were John Hay (d 1861), William Hardie Hay (1813-1900) and James Murdoch Hay (c1823-1915), three brothers who had been born and brought up in Scotland but settled in Liverpool, although their choice of residence did not preclude much of their work being in their native country. Themselves ‘liberal in theology as in politics’, most of the many Scottish churches they designed in the 1850s were for congregations of the Free Church of Scotland, then busy replacing the cheap buildings they had erected immediately after the Disruption of the Church of Scotland in 1843.

However, the Hays were not sectarian and, between 1850 and 1855, had designed a number of Anglican churches in England and, in Scotland, the Episcopal churches of St John’s, Perth, Christ Church, Trinity, in Edinburgh, and St Andrew’s, Callander. Almost all their churches, regardless of denomination, were in the 14th century Decorated Gothic style favoured by Catholic-minded Anglicans and Episcopalians but the planning of these churches, even those built for Anglicans, was half-hearted in its emphasis on the importance of the altar which the more Catholic-inclined preferred to be placed in a clearly defined chancel separate from the choir.

For Hibbs’ new chapel they designed a relatively broad nave and north aisle, together planned to seat 450. The lower chancel was largely occupied by stalls for the clergy and choir and much of its north side taken up by an arched recess for the organ, only a short sanctuary (or ‘sacrarium’) raised a single step above the choir being provided for the altar. At the west end of the chapel’s north side was placed a porch, its inner angle with the nave filled by a small tower which containing a stair to the west gallery, its pyramid roof substituted during construction for the more expensive and taller spire-topped belfry shown in the Hays’ original design.

The interior was simply furnished, with plain pews in the nave and, in the chancel, slightly more elaborate choir and clergy stalls and a wooden altar. The elaborately traceried large east window’s central lights were filled with stained glass (Christ Teachest Humility) later in the 19th century but something of the sort was probably intended from the start.

Opened as Christ’s English Episcopal Chapel in 1857, the new chapel was quickly renamed the St Vincent’s Chapel, not in honour of one of the saints of that name but after the street which commemorated Admiral Lord St Vincent and in which it stood.

Hibbs himself stayed in Edinburgh only until 1860 when he returned to England, having accepted a living in Gloucestershire. Much longer was the incumbency of his successor, Thomas Talon, an Irishman who had served as a priest in England for twenty years before coming to St Vincent’s in 1867.

Ten years after Talon’s arrival the Association of English Episcopalians was founded, grouping as a quasi-denomination those Anglican congregations in Scotland which, like that of St Vincent’s, regarded themselves as in communion with the Church of England but not the Scottish Episcopal Church. The Association obtained the services of Bishop Edmund Beckles, a retired Church of England missionary bishop to Sierra Leone, for episcopal ministration, apparently in the event limited to confirmations. Unsurprisingly, the Scottish bishops complained of this ‘intrusion’ into the affairs of their province and in 1884 Beckles was censured for his actions by the Convocations of York and Canterbury. This disavowal of the ‘English Episcopalians’ by the Church of England was probably expected and, two years before, Talon and the St Vincent’s congregation had joined the Scottish Episcopal Church, although retaining use of the English Book of Common Prayer at all services and adhering to a generally Evangelical theological and liturgical position.

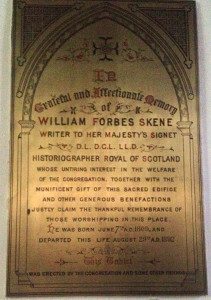

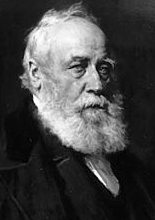

Influential in this decision was the historian of Celtic Scotland, William Forbes Skene, a leading member of the congregation of St Vincent’s where he is commemorated by a prominently placed memorial on the south wall of the nave. Skene had bought St Vincent’s in 1875 ‘as a Memorial of my dear Father and Mother, James Skene of Rubislaw and Jane Forbes his wife’ and conveyed it to the Vestry in 1883. He stipulated that if the Church ever had to be sold that the proceeds be used to build another church within the Diocese of Edinburgh.

Skene, an avowed Evangelical, argued that, since the Scottish Episcopal Church’s General Synod of 1863 had established the English Book of Common Prayer as the primary authority for the Church’s worship and the Scottish Episcopal Church had adopted the Church of England’s Thirty Nine Articles as a doctrinal yardstick, for St Vincent’s to remain outside that church could no longer be justified.

Talon retired in 1888 after twenty-one years of service to St Vincent’s. The next two incumbents, Thomas Brackenbury and Percival Hulbert, were both English imports with no previous experience of Scotland. They were followed, in 1907-16, by two Canadians, one of whom had served a brief curacy in Edinburgh at St Paul’s, York Place. By then there had been established a pattern of worship at St Vincent’s which was to continue until the chapel was acquired from the Vestry by the Order of St Lazarus in 1971.

Celebrations of Holy Communion were held at 8 (or 8.15) a.m. and 12 noon, Sung Matins at 11 a.m. and Evensong at 6.30 p.m. There was a surpliced choir but eucharistic vestments were not worn by the clergy. The longest-serving (1917-34) of the 20th century incumbents was Alexander Ewing who, after serving curacies and teaching at preparatory schools in England, had come to Glasgow in 1914 as curate to St Silas’ English Church before joining the Scottish Episcopal Church as a curate at St John’s, Princes Street.

His successor, Charles Mason, had been an undergraduate at Edinburgh University but trained for the priesthood at the Anglo-Catholic St Stephen’s House, Oxford, served a curacy in London and then spent over twenty years in India and Aden. After his death in 1943, St Vincent’s acquired its first wholly Scottish incumbent in George Gunn, who had trained at Edinburgh Theological College and served curacies in the Glasgow diocese. However, he left after four years to take charge of New Pitsligo and, later, St Luke’s, Dundee, both churches higher than St Vincent’s in their churchmanship and, perhaps, closer to his own.

Of the next two priests, one, Thomas Martin, had been educated at Trinity College, Dublin, and served as a curate in England before coming to St Vincent’s. The other, Neil Gordon-Kerr, had been at Edinburgh University and the Low Church Wycliffe Hall, Oxford, and a curate and vicar in Yorkshire for eighteen years, although also Rector of St Anne’s, Coupar Angus, for a couple of years.

It was during this period that Anne Clutterbuck first attended St Vincent’s. She recalls: ‘I went to matins mostly – all the services were simple and quiet but we usually had good organ music. Most of the congregation came from Stockbridge and were elderly. I used to leave the baby in her pram in the passage and the elderly verger would let me know immediately if she woke.’

Jessie Smith attended St Vincent’s from the late 1940s. Before her marriage there in 1953 she had already started a Sunday School. The congregation was very small and the Sunday School equally so. It took place during the service, was held in the vestry at the back of the Chapel and usually lasted 20 minutes. As with many Sunday Schools, outings were arranged to places such as Burntisland or North Berwick but often included many of the adult members of the congregation. Sometimes a lorry would be hired and everyone sat on its floor for the trip.

In 1960, Charles Crichton was appointed Curate-in-Charge of St Vincent’s. Nearing retirement age, he was also the Diocesan Supernumerary and Hospital Chaplain. The burden of occupying all three positions may have contributed to his death five years later after which services in St Vincent’s were conducted by clergy from St Paul’s & St George’s, York Place. By this time the Sunday School had ceased to meet.

In 1971, St Vincent’s ceased to be a church within the Diocese of Edinburgh. The building was sold to Lt Col. Robert Gayre of Gayre and Nigg. The proceeds were put by the Diocese to the Livingston Mission. Following this some alterations were made. The most notable were the blocking off of the north aisle to form a chapter house for the Order and the insertion of a wondrous display of heraldic stained glass, all by A. Carrick Whalen. In 1987 Lt Col. Gayre disponed St Vincent’s to the Trustees of the Commandery of Lochore of the Military and Hospitaller Order of St Lazarus of Jerusalem to continue its use as its private chapel.

An organ by Thomas Christopher Lewis of 1889, originally built for the Earl of Aberdeen’s London house, rebuilt by Eustace Ingram in 1897 for Christ Church, Trinity, in North Edinburgh, was installed in the gallery by Ronald L. Smith in 1981. The gallery itself was extended, the space below intended partly for use as a refectory by the Order. After the acquisition of the Chapel by the Commandery, St Vincent’s became the setting for its ceremonies – but continued also to be used for Episcopalian Sunday services, although now, as stipulated by the Commandery, according to the Scottish Liturgy of 1929. The chapel’s already-established small choir remained in existence until the late 1980s when several of its members moved out of the area.

Services were conducted by a succession of retired priests. The first was the Reverend Herbert Coles who, after serving a curacy at the Anglo-Catholic church of St Hilda’s, Hartlepool, and a year as a missionary in India, had come to the Edinburgh diocese as priest-in-charge of St Ninian’s, Comely Bank, in 1928 and had later worked as Diocesan Supernumerary and Hospital Chaplain, for two of these years in association with the Reverend Charles Crichton.

Father Coles was succeeded at St Vincent’s in 1975 by the Reverend David Lumgair who, after service in banking and the Royal Air Force, had been ordained when over fifty. Part of his training for ordination had been at the Edinburgh Theological College and he served a curacy at St Mary’s Cathedral, Edinburgh before moving as a vicar to England. After his retirement in 1973 he moved to Edinburgh where he ministered as chaplain of St Vincent’s and Dean of the Order of St Lazarus from 1975 to 1977.

He was followed at St Vincent’s by Canon Malcolm Clark who had just retired after twenty-one years as Rector of the Church of the Good Shepherd, Murrayfield.

Remarkably, Canon Clark’s chaplaincy at St Vincent’s was to last for a further twenty-one years, ending only when he was ninety-three. In the latter years of his ministry the Hereditary Commandery of Lochore had ceased to use the Chapel, although retaining ownership of the building, and attendance of others at the Sunday services had dwindled to a handful.

On Canon Clark’s eventual retirement Canon Rodney Grant, for many years Rector of St James’, latterly St Philip & St James, Inverleith, and recently retired, took over as priest-in-charge of St Vincent’s.

Over the next ten years the membership of the congregation almost tripled and facilities such as storage cupboards for vestments and the kitchen and disabled-access toilet were upgraded. The 1929 Scottish Book of Common Prayer remained as the staple of worship, with the 10.30 a.m. Sung Eucharist and 6 p.m. Sung Evensong the principal Sunday services. On 10 May 2014 the Congregation of St Vincent’s formally entered the Diocese of Edinburgh again. A service was held to mark the event. However, the ownership of the building did not change.

He was succeeded, as Rector, on St Vincent’s Day, 22nd January 2015, by a former Provost of Oban Cathedral, the Very Reverend Canon Allan M Maclean. He and his family were already well known to the congregation.

On 18 June 2018 Reinold Gayre, Colonel Gayre’s son, offered to return St Vincent’s Chapel and its endowment fund to the Vestry in an unexpected and generous email to Canon Allan Maclean and the Hon Barnaby Miln, the Vestry’s Property Convener. Reinold Gayre and Barnaby Miln had been in regular touch for some time concerning the Commandery’s responsibility for the upkeep of the church building. The Vestry warmly accepted the gift and instructed its solicitors to act on its behalf.

A Declaration of Trust and Deed of Appointment was signed on 5 June 2020 pending completion of the conveyancing of the church building – at which point the Commandery of Lochore would be dissolved by its lawyers.

Illustrated Booklet

An illustrated booklet about St Vincent’s was prepared by members of the congregation including Andrew Milner, the late John Gifford and the late Roy Wilsher, with an introduction by Bishop Brian Smith, sometime Bishop of Edinburgh. The booklet contains a short history of the church and of the Order of St Lazarus, which used the church for many years, and information about the heraldic decorations which were installed by the Order. Copies of the booklet are priced at £3.00, and are available in the vestibule, payment to the Donation Box nearby.