Losing ourselves in Lent

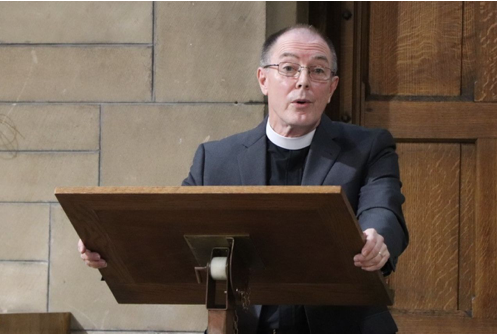

The Reverend Dr Michael Hull writes:

Lent marks our preparation for Easter Day. As liturgical seasons go, it is one of the earliest in recorded Christian history. Lent has been observed from the second century, and by the fourth century it was observed for forty days, marking the time backwards from Easter as its terminus ad quem. To borrow from the final line of Charles Wesley’s hymn ‘Love Divine, All Loves Excelling’, Lent is a time for us to be ‘lost in wonder, love and praise’.

We often speak of losing ourselves in a positive sense, of becoming absorbed by someone or something. We lose ourselves in people, in experiences of nature, in books and so on. Lent is a time to lose ourselves in Jesus and the Atonement. Whilst it is true that Lent entails the staples of prayer, fasting and almsgiving, Lent is about them only insofar as they allow us to be lost in awe and imitation of our Redeemer. The entreaty formulated by St Francis of Assisi expresses it well: ‘We adore thee, O Christ, and we praise thee, because by thy holy Cross thou hast redeemed the world’.

The prescribed lections for Ash Wednesday would have us lose ourselves in God. The Prophet Joel (2.12–17) calls us to return to God with all our hearts and ‘rend our hearts not our garments’. In other words, Joel’s emphasis is on self-examination and soul-searching. That is not to preclude public prayer, fasting and almsgiving, to be sure, but it is to underscore the nature of the interior conversion they signify. It is noteworthy that life in ancient Israel was, perhaps, not so different from life in our own day in terms of virtue signalling. Fasting, weeping and mourning in days of yore done for all to see is akin to sporting chic clothing indicative of a good cause to which we may (or may not have!) donated or in our determinedly speaking of righteousness as if others were unaware of it. Joel would have us lost in God, not in ourselves. The same point is made by Jesus in Matthew (6.16–21). Jesus tells us not to be hypocrites, the virtue signallers of his day. Jesus tells us to be unconcerned with what is seen by others. What God sees is what counts. It is mistaken to presume that Jesus’s words apply to the first century and not the twenty-first century. Jesus is speaking to you and me to remind us to get over ourselves and to get into God in wonder, love and praise.

Lent gives us a fixed season for losing ourselves along a pattern established in salvation history by figures no less than Moses and Jesus. Exodus 34 (cf. 1 Kings 19.8) recounts Moses’s rewriting of the Decalogue and remaining with God on Mount Sinai for forty days and nights. This mysterious and transformative period leaves Moses changed. His face shines from his encounter with God. Jesus also spends forty days and nights apart in the desert. The experience is recounted in Matthew (4.1–11), Mark (1.12–13) and Luke (4.1–13). It is alluded to in the Letter to the Hebrews (2.18; 4.15). We refer to it as the ‘temptation of Christ’, and surely it is that, yet the encounter with the devil is a period of preparation, for it is after it that Jesus begins a public ministry that brings him to offer his life on the Cross to have it restored in the Resurrection. We are called to do the same: ‘Whoever loses his life for my sake will find it’ (Matthew 10.39; cf. Luke 9.23).

Lent is now upon us. The forty days have begun. Let us lose ourselves in it. We have forty days set aside for wonder, love and praise. We can lose ourselves in wonder by closely reading Holy Scripture: hearing, reading and inwardly digesting God’s revelation to us. It is, indeed, the greatest story ever told. We can lose ourselves in love by reaching out to others in corporal and spiritual acts of mercy that bespeak the theological virtue that is love. We can lose ourselves in praise of God by worshiping, especially in the beautiful liturgies of Lent, wherein we proffer God the praise that is due.

Still, we must recall that Lent is clearly oriented toward an end, a goal. We are not meant to stay lost in Lent any more than Moses was meant to stay on Mount Sinai or Jesus was to remain in the desert, even if the good that we are and the good that we do goes well beyond forty days. We lose ourselves in Lent to find ourselves on Easter Day when the promises of God are fulfilled here and hereafter.

The Reverend Dr Michael Hull has been an Assistant Priest at St Vincent’s since 2015. He is also Director of Studies for the Scottish Episcopal Institute.